Sermon by Mother Katie for 1st Sunday in Advent

Advent begins – and I think many of us like to put up the lights, bring out the chocolate calendars and start Advent as the beginning of a journey of joy towards Christmas. And in many ways there is nothing wrong with that – in fact it displays a theology of hope which I’m firmly in favour of.

But it is worth noting that traditional Advent strikes a very different key. It starts with despair – with people at the end of their tether and utterly fed up. Perhaps a more honest note for 2020 which has proved so hard for us all?

Isaiah poetically describes the people as a filthy rag – so contaminated no one will touch them, least of all God – or a faded leaf so fragile and alone that it is easily blown away from the tree it has been part of. These are a people who have forgotten their God, just as they feel he has forgotten them. They are in pain and the wait is hard.

Whilst Mark gives us his mini apocalypse with total cosmic collapse. The sun and moon go out; stars fall and angels search the earth collecting those who will survive into the next world. Which all sounds rather the script for a Dr Who Christmas Special to me.

It is an alarming – even frightening start to the festive season – not quite what you expect.

It is a start that doesn’t dress up the darkness with light – but faces the darkness head on and finds in it a gift – the gift of the presence of God himself.

The ancient Persians had a saying that only when is it dark enough do we get to see the stars.

The darkness demands action of both God and ourselves. And that action is like the heart of the Eucharist an act of remembrance. That we remember that without God we are nothing – just clay – only with God are we formed into anything meaningful, useful or of value. It is the potters hands which gilt the pot with the gold of eternal life – and so we need him – not at a distance – but here with us now – touching our lives – holding us and forming us in his hands. If it is to work at all it has to be that intimate – and maybe even as messy and painful – as Potter with his clay. So for our own part must be willing to wait in the darkness as we become what we shall be in the light – allow ourselves to bend and stretch and be moulded into the shape of Christ – we must be willing to be used to carry what God places within us – and we must stay awake to our purpose and our call.

And when this is the demand made of both God and us – to be present in the darkness – to not run from it but to wait with it – perhaps God turning up in the darkness of an occupied country, as the baby of a young unmarried woman, born in poverty and soon to be a refugee living outside the comfort of a normal life and destined to be tortured and executed should not surprise us.

The darkness has much to offer if we will dare to look.

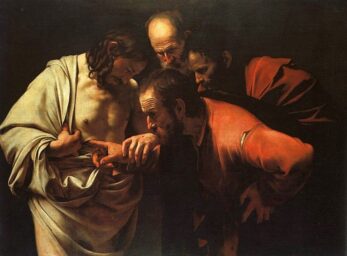

Caravaggio –was a complex and brilliant artist – who dared to look into the darkness and to use the darkness to see things more clearly.

His treatment of darkness and light in his work was revolutionary in his time. He had an almost unique ability to make us stare at the harder stuff – the reality of life rather than just the airbrushed perfection which was fashionable and desirable at the time and remains so popular over our world and social media today.

In one of Carravaggio’s most well known paintings Jesus invites Thomas to put his fingers into his still open wounds – depicting a scene from John 20.

Darkness frames the whole scene. There is no halo for this risen Christ – his white funeral clothes hold the dust of the grave – the disciples stand dressed in the colour of blood and earth with their clothes ripped – perhaps through poverty and perhaps through pain as was the custom in biblical times?

The darkness points us to the central point of light – the hand of Thomas, held by Jesus and guided by him, as it touches the open wound and goes right under the skin – in an image most of us would normally flinch from looking at. Yet, such is the gift of Caravaggio that we like the disciples look on with intense curiosity.

The face of Thomas is surprise and wonder – perhaps mixed with horror at the part he played in those wounds? But in feeling the reality of the wounds he finds faith in Jesus as Lord and God – and crucially – a God who chooses to reveal himself and his reign in the wounds caused by injustice.

Like Carravaggio’s painting the Advent calls us first to darkness and only then to the light of Christ – and the light shines not on places of glory – but places of pain and woundedness.

If we are to stay awake this Advent that is where our focus must rest too – on the wounds of the world – which remain the wounds of God. For these are the places that cry out for Emmanuel – God with us – O come O come Emmanuel.

And there we will find God present not in the perfect spaces and bodies but in the broken and the grieving – in the oppressed and the captive – in the poor and excluded.

And will discover with surprise and wonder like Thomas that is precisely in such dark places where God chooses to dwell and bring comfort and joy.

Amen.