Sermon by Sally Leeson

I’d like to begin with the end of a book. That book is Middlemarch by George Eliot, and the closing words refer to her heroine Dorothea. This woman’s quiet unselfishness and desire to do right reflects, in many ways, the sentiments of the Beatitudes. The novel ends like this… for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life and rest in unvisited tombs.

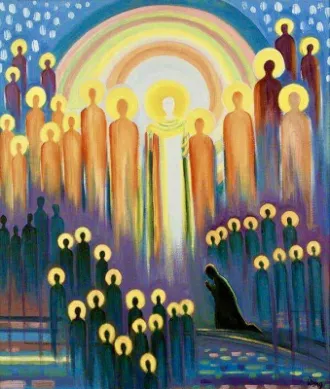

Hidden lives and unvisited tombs. Most of the lives of the saints who we commemorate today are unknown to us and unvisited by us. They are simply part of a cloud of witnesses to our faith and the transfiguring love that faith inspires. Some of the more famous, of course, are celebrated and marked by stories, icons and dates, and were even an excuse in the past for a day off work. But with both the hidden lives and the more celebrated ones, can come a degree of ambivalence. How do we measure up to their perceived holiness? Just the word saint can sometimes alienate us from their humanity, and be hard to weave into our own lives.

The author Iris Murdoch, said that it was very difficult to write about good people. She believed in The Good, but characters in her novels who are good tend to be like presences on the margin, shedding some of their light, like Dorothea is said to do, in a rather more diffuse way, a bit like perfume might spread around a room. And this seems to me to be how we often encounter the good, the saintly in others, in ways we can’t quite put our finger on but which can find expression in those simple, unhistoric acts. Desmond Tutu says he’ll never forget the time when the priest Trevor Huddleston as he walked by his mother for the first time, doffed his hat to her. This was not the thing a white man in South Africa would have normally done, and of course, the gesture wasn’t empty. It communicated something much more about the man whose head was under that hat and whose hand removed it, a man who Nelson Mandela said had done more than any other white man for the cause of justice in that country. It communicated something transformative in the life of the young Tutu.

Similarly, I’ll never forget hearing a woman-several years ago- who spoke at an event put on by the Forgiveness Project. She described visiting a young lad who’d fatally stabbed her own son. Both young, just in different gangs or belonging to different territories or schools, I forget now which. Just a child, she said, and the first thing he said to me when he saw me was, ‘Please don’t hate me.’ God only knows what her visiting meant to that lad and what it has done for him since. And what it has done for her. I’ve no doubt that her testimony affected the people listening to her. It certainly affected me. Different aspects of the light of goodness rub off on people and bring them into that light.

So perhaps in writing or thinking about saints, both living and dead, we could say that we don’t quite know where they begin and end. Their saint qualification, if you like, can’t be boxed up because the important thing is about their lives, and those lives will, like our own lives, be surrounded by other people, their goodness and their struggle.

We don’t wait in the wings, practising our holiness with the right lines and then walk out into the spotlight and take all the applause in a performance without scenery or other characters. Saintly people seem to realise that the part they play on the stage of life is only possible because of what they have learnt through others and through their lived experiences, both good and bad. It isn’t a solo act. And, of course, the religious among them will say that it doesn’t come from them anyway, but from God.

Even Jesus asks, ‘Why do you call me good? No-one is good but God alone.’

So because we don’t quite know where things begin and end, or where we might begin and end, one way of seeing today, I think, is as a celebration of participation, participation in the world in which we all have a particular part to play. And in a culture which seems to get distracted by celebrity and newsworthiness, I’m with George Eliot on her championing the hidden lives. Those lives which in her words, widen the skirts of light and make the struggle with darkness narrower. She doesn’t claim these lives account for everything. Half owing, she writes, partly dependent. There’s room for more.

And that more, for people of faith, is to see things against a backdrop of eternity, that we are participating in something beyond the confines of time and the grave. A saintly kind of discipleship is not dependent on great actions or heroic deeds, though it doesn’t necessarily preclude them. It’s about desiring the good, praying, waiting, thirsting, mourning and showing mercy. It’s about taking off your hat as a white man to a black woman in apartheid South Africa, or visiting the lad who was the source of your traumatic bereavement. It’s about making God’s love transparent. And the witnesses and receivers and bearers of that love release something we are celebrating today- our connectedness with each other and with the Divine. As Thomas Merton put it, Love is the door to eternity, and he who loves plays on the doorstep of eternity.